When The Music Stops: Why Diversification Is Key

Everyone wants to own Nvidia. Or Microsoft. Or Apple. And for good reason -- these stocks have been generational bellwethers.

The good news is: Almost everyone I know already own these stocks, whether they realize it or not.

Own SPY? → You have 8% Nvidia and 7% Microsoft allocation

Own VOO? → You have 8% Nvidia and 7% Microsoft allocation

Own IVV? → You have 8% Nvidia and 7% Microsoft allocation

Own QQQ? → You have 10% Nvidia and 9% Microsoft allocation

You get the point. By the way – if you own all of these S&P 500 ETFs, it’s essentially the equivalent of going to a restaurant and ordering the cheeseburger, a hamburger with cheese, and a cheeseburger with extra cheese (hold the tomatoes). Don’t conflate this for diversification, because each fund is nearly identical.

So the question really is – how many cheeseburgers do you really want? How much of your total portfolio should be Nvidia or Microsoft or Amazon?

Researcher Antti Petajisto and his data set will tell you: no more than ~10% allocation to any one particular holding.

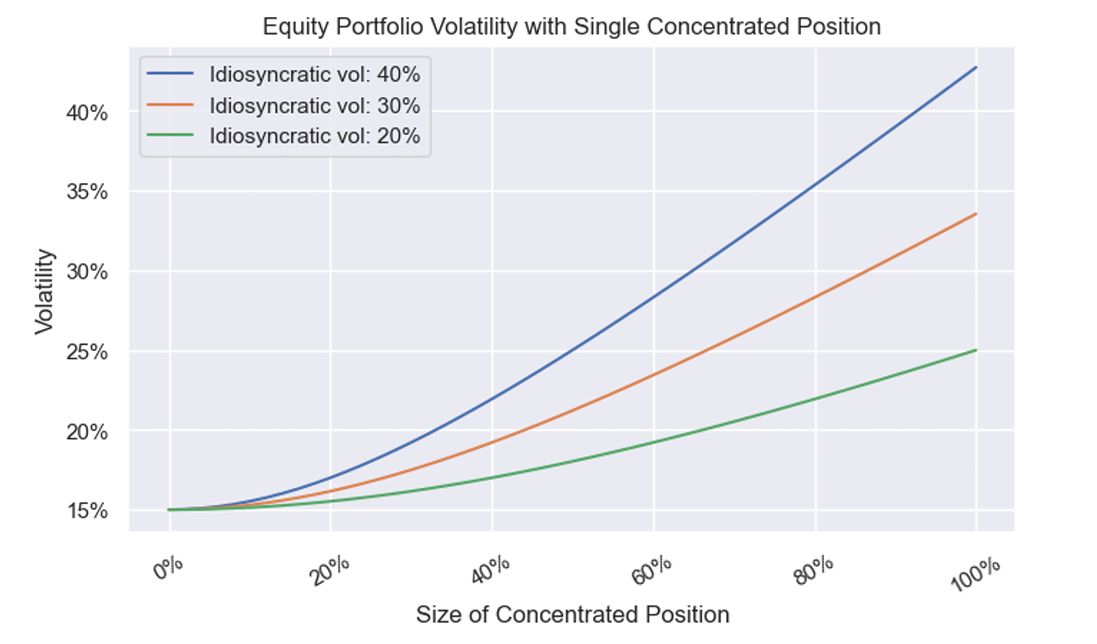

Petajisto found that "portfolio volatility is essentially unaffected by holding a single position at weights between zero and 10%” and that “the effect on portfolio volatility starts to become meaningful at single-stock position weights of 10-20%”.

Translation: With a concentrated position of up to 10% of your portfolio, you’re unlikely to introduce excess volatility (“idiosyncratic risk”). But once you cross that 10% threshold, you begin to introduce risk that you’re no longer getting compensated for taking. That basically means that you are making bigger gambles – not investments – that are statistically unlikely to pay off.

In this graph, the different line colors represent concentrations of stocks with higher or lower volatility. We see these lines begin to diverge at around ~10% on the x-axis, demonstrating the excess volatility.

"But Josh, I would have massively outperformed the market if my portfolio had just held the Magnificent 7 (Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Meta, Tesla, Google) over the past few years."

You're absolutely right. And you would’ve taken enormous risk. True — a handful of outlier stocks have massively over-performed the broader market. But don’t conflate the outcome for the strategy.

The data would also say that, eventually, you will be wrong.

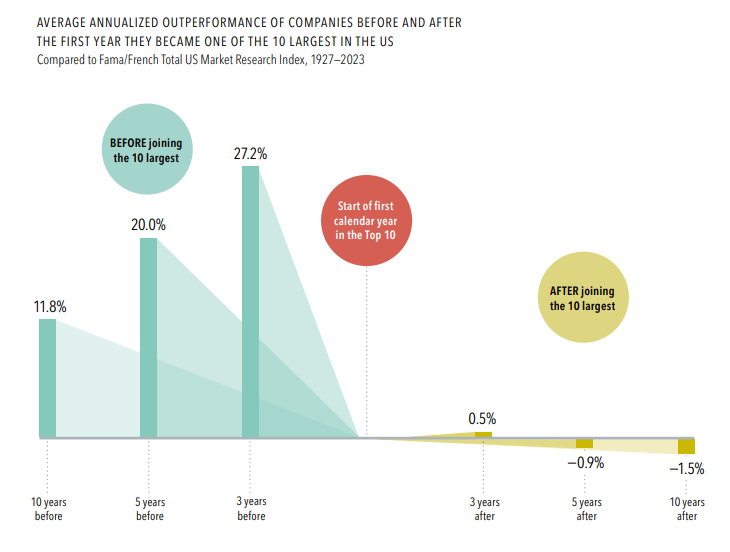

Even the best performing stocks don't tend to outperform for long.

This data from Dimensional Funds suggests that once a stock enters the top 10 by market capitalization, its ability to continue outperforming the market drops significantly – to the point where, within 5 years, these stocks tend to actually underperform the broader market.

It’s hard to remember when any other companies, aside from the Magnificent 7, comprised the Top 10 of the S&P 500.

But, as the chart, below, demonstrates, the list does shift. Every single one of these companies was thought to, at one point, have an impenetrable economic moat.

It would also seem like the 2025 companies have impenetrable economic moats these days. But what will the Top 10 holdings look like in 2030? Will OpenAI leapfrog to the top of the list? What about some no-name humanoid robotics company? NVIDIA, for example, was close to a no-name company nearly 5 years ago. It’s impossible to say what will happen. But only a truly diversified portfolio is likely to capture some of that unknown for you.

So is the S&P 500 truly diversified?

I see a lot of folks with the majority of their portfolios in S&P 500 ETFs. This strategy has worked incredibly well over the past few years -- but it carries a lot of risk in that it’s hyper-focused on Large Cap, predominantly Growth-oriented, US-based companies.

What does the data tell us? Large Cap hasn’t historically outperformed Small Cap over the long-run. Growth hasn’t historically outperformed Value. And the US hasn't always outperformed International.

Most Millennials don’t remember the “Lost Decade” of 2000-2010 when the S&P 500 actually had negative total returns (we have “recency bias” to thank for that).

We don’t know what the future holds.

We don’t know whether AI will continue to rip or if AI is really just the next big bubble that promises enormous returns, but delivers empty-handed.

We don’t know which geography/market cap weighting/sector will ultimately yield better or worse returns.

Here’s how sectors within the S&P 500 have historically performed (in case you were wondering, there is no pattern):

When officers in the military are tasked with making battlefield decisions, the military doesn't evaluate them on the outcome of the mission. Rather, they are evaluated based upon how well they made data-driven decisions.

The same is true when building a portfolio. Most stocks underperform. Most over-performing stocks don't continue to overperform. Sector performance varies by year. And even geographical performance varies year by year. We know what the data says.

Now is a good time to really dig into your portfolio (or have your financial advisor do it for you!). Are you diversified across markets? Sectors? Geographies?

When you’re fully diversified, you’ll both always have regret and you’ll never had regret -- which is exactly the point. Consistent, "good enough" returns, year-over-year, is how the power of compounding works it's magic. And that's how you get wealthy.