How I think about the equity vs. salary trade-off

Before transitioning to financial planning, I worked in tech where I, too, received different types of equity grants from my employers – Incentive Stock Options (ISOs), Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs), Restricted Stock Units (RSUs), etc.

The truth is that, on one hand, it’s a great feeling to have an equity stake (or, at least the option to buy into an equity stake) within a company that is seeking to disrupt the world and/or build something cool. Plus, since you’re already burning the midnight oil and generally putting a lot of blood, sweat, and tears into this company it’s nice to have equity that *could* be worth a chunk of change down the line.

But on the other hand, it’s pretty much impossible to find a specialist who can help you strategize around your equity compensation. When should you exercise? When should you sell? What are the tax implications of each? Which tranches of shares do you prioritize? When do you just let your equity expire and walk away from it?

These are the questions that I pondered myself when I was in tech. And I couldn’t find someone who was both an expert in tax strategy and who understood my Millennial tendencies. So I started my own firm, Presidio Advisors, to do just that.

Enough about me. Let’s talk about a question that I get frequently, which is: “how do I think about the tradeoff between salary and equity compensation?”

Let’s tackle this question in two ways:

What does the data tell us about the performance of startups over time?

How do I minimize regret?

1. What does the data tell us about the performance of startups over time?

As it turns out, the data is pretty much unequivocal: market returns are generated by outlier companies.

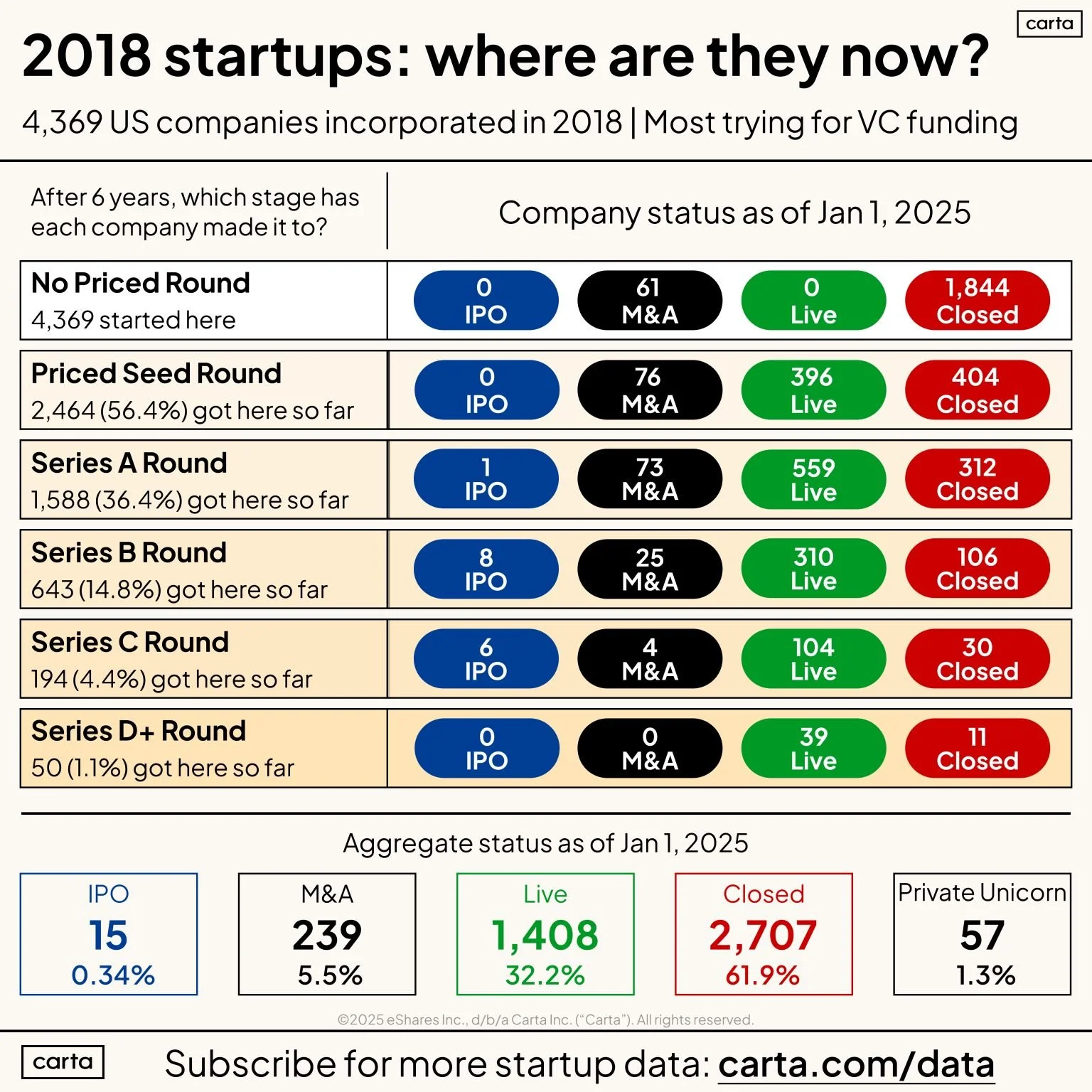

Carta looked at ~4,400 companies that incorporated onto their platform in 2018 to see how they’ve fared over the past years. The data is stark:

62% of companies have formally shut down.

32% of companies are “live” (although a ton are hanging out in the Seed and Series A rounds, which makes one wonder if they are really just “zombie” companies at this point?).

6% have been acquired (but we don’t know if the acquisitions actually provided any economic value to common shareholders).

1% are now valued at $1B or more (LFG!).

And fewer than 0.5% have IPO’d.

What’s even more stark is that if you calculate the percentage that have closed after each round, it consistently hovers around 15-20%. Even the Series D+ companies that have time and again demonstrated product market fit are shutting down at a rate of 1 of every 5 companies or so. So if you thought that your company just needs to cross the chasm from Series B to C and then you’re all good…well, this data suggests otherwise.

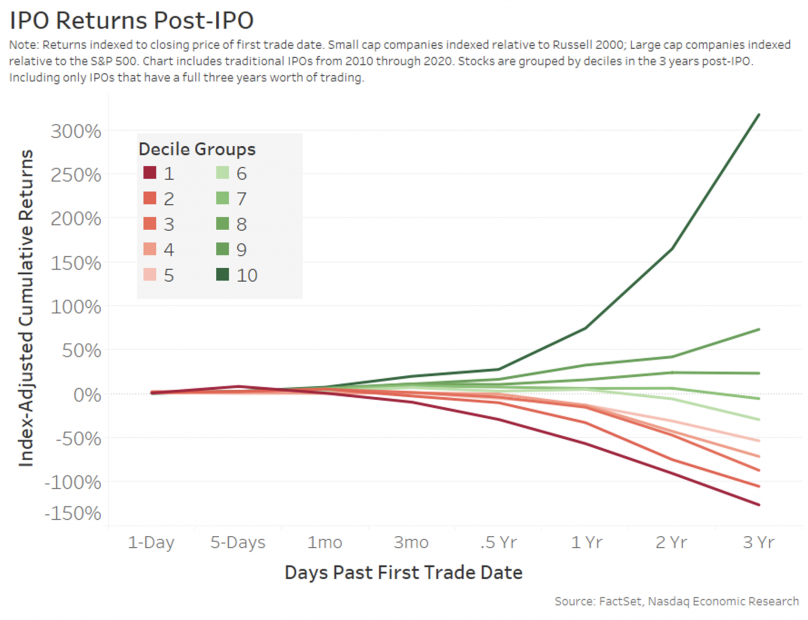

What about post-IPO companies? If your company is fortunate enough to IPO, should you HODL (Hold On for Dear Life)?

Here’s what the data shows (see chart below): once again, market returns are generated by outliers. There is typically a nice initial bump on the first day of trading. And then, within 3 years, there is a group (~10%) of post-IPO companies that are absolutely killing it, relative to their broader index. These are the usual suspects that you’ve all heard of.

But there are also ~70% of post-IPO companies that are drastically underperforming the market. And, in fact, they are performing so poorly that they’ve almost wiped themselves out entirely.

So here’s the gist: startup equity is a lottery ticket. It’s upside only. You have to treat it as upside because, statistically, the odds aren’t great. And, even if your company beats the odds and is able to IPO (or have some other liquidity event), the data is clear: market returns are still generated by outliers.

Now that you think I’m a permabear and class-half-empty kind of guy, perhaps you’re cynically muttering to yourself: if the upside is so few and far between, why bother working at a startup in the first place?

Lots of reasons, actually. You gain valuable leadership experience. You get to rub shoulders with industry leaders. You move fast and break things. You are forced to make tough decisions. You have influence at the highest levels of the organization. These are all unsung benefits.

And, the data (can you tell that I love data?) backs this up: a 2022 article out of Harvard Business School entitled Why A Failed Startup Might Be Good for Your Career After All noted that “the market values the experience [founders] have and rewards them in terms of high seniority, high prestige positions, even though they failed.”

So that’s the data component that I think is important for everyone at a startup to internalize. Once you’ve internalized that data, the question then becomes “how do I minimize regret when choosing between salary and equity?”

2. How Do I Minimize Regret?

Decisions pertaining to equity compensation are complex. And there often is no one right answer. Which means that the likelihood that you have some sort of hindsight regret about your decision is basically guaranteed. I’m sure there are zillions of stories about Amazon shareholders who cashed out in the early 2000s...only to look back and think “if only I had held on to those shares…” And on the flip side, there are definitely stories of Intel/Yahoo/General Electric/Zoom/Peloton/you-name-it shareholders who held on for too long and are thinking “if only I had sold when they hit their peak valuation…” Worthy of note – there are WAY more “wish-I-had-sold-earlier” stories than there are the “wish-I-had-held-longer” stories.

Here’s how I think about minimizing regret: each of us are in different stages of our lives. Some of us have student loan debt. Some of us have kids that we need to feed. Some of us are trying to buy a house. Some of us lived through the 2008 financial crisis. Some of us are young, dumb, and eager for maximal risk/reward.

Each of us, therefore, has a different risk tolerance – that is, how well can we sleep at night without feeling queasy. And, each of us has a different risk capacity – that is, how much volatility and risk can our portfolios quantitatively handle before we permanently destroy wealth.

In considering both your risk tolerance and risk capacity, the question to ask yourself is: what would you regret less?

You optimize for higher salary, but the company valuation skyrockets and goes to the moon

You optimize for greater equity, but the company fails entirely

If you use the data from above and combine that with an understanding of your risk tolerance, risk capacity, and regret minimization framework, then you’ll have optimized this equation more than the vast majority of people ever will.

The last data point here is that no matter what decision you end up making, this isn’t the “end all, be all”. Data from Carta also shows that ~70% of startup employees who stick around to the end of their initial equity grant (typically four years), will receive a refresh grant.

So let’s extrapolate that a bit: if your company is doing well → you’re probably going to stay for longer → if you stay for longer, your company will probably give you a refresher grant which will boost your equity → and if you stay for longer you’re probably up for promotion at some point, which will likely increase your salary.

Some concluding thoughts.

In the end, if your company has a “successful” liquidity event, you’re going to be just fine. I promise.

And on the flip side, if things don’t work out (statistically high probability), let’s make sure that you’ve given careful thought to the regret minimization framework. You may not cash out in the way that you had hoped, but you’ll at least have had some good learnings and the satisfaction of knowing that you made the best decision you could’ve made with incomplete information.

Someone once told me that the military doesn't evaluate an officer's battlefield decisions based on outcome. They evaluate battlefield decisions based on the data that the officer had at that given moment.

This is exactly the same approach that you should consider when evaluating the decision to optimize for equity or salary. The outcome isn’t important. The data that you had at the time is important.

If you or someone you know needs help with their tax or equity compensation strategy, feel free to reach out or connect with me on LinkedIn. I post frequently, write a blog, and am happy to generally be a sounding board to folks.

Best of luck out there!

Josh